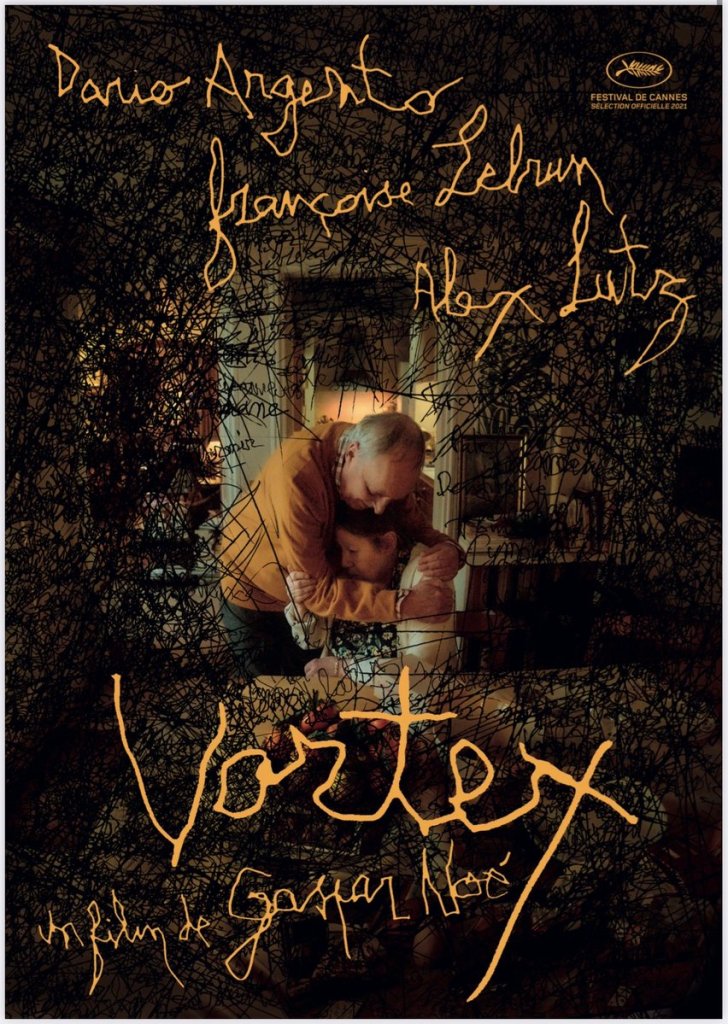

France’s resident moviemaker/troublemaker Gaspar Noé (“Enter the Void”; “that movie where Monica Bellucci gets raped for ten minutes”) has a new movie out called “Vortex” . It’s one of the best new movies I’ve seen in the last 10 years. That’s a mean feat. Discuss:

Vortex is about a small family – an elderly couple, living alone; and their son – dealing with the late-stage dementia of the matriarch. And while in many ways it – aesthetically & thematically – slides nicely into the controversial director’s filmography at this point in his life (he’s turning 60 next year), it’s also unique amongst his back-catalogue. In this way and others, it’s sure to draw comparison with Michael Haneke’s 2012 movie “Amour” (also about an elderly couple and their offspring dealing with the deterioration of the wife). With Amour, a well-known & incendiary director took his unique cinematic language and translated it successfully to a serious, contemplative “chamber piece”. I’ve always wanted to call a movie a “chamber piece” and now I can. Twice! Vortex is a “chamber piece”: a serious-toned character drama in-and-around one location.

But while Haneke’s film (translated as “Love”) was about the love and helpless devotion of the husband to his wife’s condition, the unnamed wife in Noé’s film is neglected by her live-in beau (legendary horror director Dario Argento, acting here) who has had one foot outside of the marriage for at least the last third of their time together, well before her deterioration. The wife (played thanklessly by Françoise Lebrun: we never once get to see her as anything approaching lucid) wanders their enormous Parisian flat – hoarded with heirlooms & the man’s book collection – with no supervision while her husband shuts himself in his office, dreaming. He dreams of a time before his wife’s illness; of a new book he hopes to write (about “film, and dreams”); and of the love he has for a mistress who’s losing interest in him. But while he’s able to keep himself occupied in his old age with hobbies and fascinations (he’s far from healthy, himself), his wife can’t even keep up the homemaking, and without anything else to keep her mind busy her condition deteriorates rapidly while the two men in her life argue over next steps. It’s in this situational nihilism where Vortex finds its similarities to Noé’s other feature films, where none of the main characters do themselves any favours (especially the son) and things are so far gone they can only end in disaster.

However, this time around it’s different. Vortex is special. Really special. I’m still thinking about it, deeply. I’m dreaming about it. Make no mistake, it is a depressing movie. Like, really sad. REALLY sad. Not the kind of sad where you want to go off and have a good cry about it. It’s the kind of sad where your soul feels empty after watching and takes days to refuel: where you sit in the empty theatre way past lights-up in stoic silence. The last time that happened to me, it was from “United 93” in 2006, when my friends & I were so upset after the screening that we stayed too late & they closed the theatre around us, and we had to get security to let us out. True Story. And while I didn’t stay that long post-credits this time around, the rare emotional reaction I had is why Vortex is special. Apparently it was conceived after Noé nearly died from a brain aneurism, and it’s the urgency of the filmmaker’s own self-preservation that makes the work so raw & relatable. That is, if you submit to his usual list of artistic conditions. This time, though, they don’t include full-frontal masturbation; casual horse butchery; thirty-second countdowns to incest; and roller-coaster camerawork. This time, Noé asks his audience to be patient: possibly the most challenging of the virtues.

More even than his usual visual trickery (the much-touted split-screen presentation) will Noé’s film challenge its audience with its pace. Personally, I didn’t have a problem with it: I was gripped. Every minute the wife was left alone, whether it was pulling out an ironing board or cleaning up her husband’s office, I sat in dread of what was coming; and every time another montage played of her wandering around the apartment – alone and in the dark – while her husband isolates himself from her, or goes to a party without her & without arranging a sitter, I was appalled at her living condition. Her illness didn’t happen overnight: was he really THAT selfish & stubborn that he let things get so bad without addressing them early enough? As the overburdened husband, Argento successfully generates apathy without taking away from the character’s own personal side-story of shame, regret, and guilt. As far as the pacing is concerned, from a narrative perspective every scene pulses & breathes and never once did I think there was something Noé was showing me that didn’t need to be there. Like last week’s “Cabaret”, Vortex’s pacing could be attributed to the symbolism of passing time, or of “life itself”. With Bob Fosse’s film however, where the overarching theme about “life simply happening” was a cop-out, here it’s the truth, so it works. This is well-illustrated in the aforementioned “office clean-out” sequence, where the husband’s frailty in body & his wife’s in mind clash most-unfortunately. Vortex could even have been longer: particularly in the back-half, where Noé flashes-forward a bit quicker through the wife’s final days than I would have liked (although this, again, was probably a stylistic choice).

Back to Haneke: when I first watched 1997’s “Funny Games”, I fast-forwarded through the “grieving” scene because nothing was happening. In that way, Haneke won. Not that watching a movie has never been a game between viewer & creator (a good mainstream example is David Fincher’s work up until “Panic Room”), but where Funny Games was concerned, Haneke had proved his point. I was so desensitized to the violence (the main draw of watching the film in the first place), that arguably, when the “real” pain started post-script – the after-shock; the tears; the bargaining; the stuff you don’t see in mainstream movies – I wasn’t interested. It was boring. To him I said “well-played”. Noé likes to toy with his viewers, too. During “Irreversible”‘s rape scene, I started looking at my watch and wondering when it was going to be over, but not in the way where I was horrified & wanted it to stop: it went on too long and I felt the scene had overstayed its welcome. Ergo, Noé proved his point, and in that instance, he won. This time around, there isn’t a single scene (other than possibly the first & final minutes) that could be deemed “trademark Noé”. Single shots, maybe, but not any sections that stood out to be particularly shocking or nauseating: just the underlying & feature-length sense of each of the three main characters’ despair, whether unintended (the wife), self-righteously (the husband), or self-sustainably (the son). There were times I looked over at my Dad – who came with me & who is 70-years-old – and he was looking at his watch, bored. Noé won against both of us, for different reasons.

Your mileage, as always, will vary. There were many parallels between what happened in the movie and what I went through with my wife looking after her Dad, before he died. My father has many of the traits of Argento’s father figure. I have many of the traits of the son. Noé strives for a gut-reaction from his viewers, and mine was visceral. The world of cinema can rest assured that there have now been at least two excellent & diametric films dealing with aging & death in the last 10 years, and both from France. If you have the constitution, Vortex could change your life. Not least of which, it should inspire conversation: not just with fellow film buffs, but serious talks with loved ones. Talks that should happen while your partner can still communicate back.

//jf 6.8.2022

Movie poster sourced from Reddit.