A spoiler-free movie review.

2 out of 5

It’s a mistake to confuse pity with love.

Stanley Kubrick’s second narrative feature “Killer’s Kiss” is a remarkable step-up in quality from his first film “Fear and Desire”, but it still ain’t no Georgia peach.

We’re talking about movies that are closer now to their centennial anniversaries than ever before, and unless you’re a Film Major in post-sec, or doing research, or you’re an old soul & actually enjoy watching older movies (the minority), or a senior (the majority), as we move further and further into the foreseeable future, it’s less likely that ensuing generations will seek out a black & white film from the 1950s, out of a largely-chauvinistic & misogynistic body of work, even if it IS a Kubrick film. Why watch this when you could watch “Full Metal Jacket” again, and possibly catch something you missed the first dozen times around? Is there even a reason to watch Killer’s Kiss in the 2020s other than what I mentioned, or possibly to farm content for a humble blog? Hmm? Read on to find out!

My own personal audience “barometer” loves movies as close to ninety-minutes-long as possible: in an hour-and-a-half, you should be able to get to whatever you need to get to, with minimal time-wasting frou-frou. Killer’s Kiss is 67 minutes, and in that hour not once could I remove myself from the thought of it being an early Kubrick. Its plot is simpler than Fear and Desire’s, but clearer, and less abstract. The pacing is better, despite incorporating even more of that other Kubrick stand-by – the long shots – than Fear and Desire did. Killer’s Kiss looks better, with a dynamic use of shadow & light: the perks of filming on a soundstage rather than in the middle of the woods. It has a huge, epic foot chase in place of a denouement, almost twenty years before “The French Connection”. And Frank Silvera (Mac from Fear & Desire) returns as the primary antagonist: a sleazebag moustachio’d dance-hall owner named Vincent. Eyyyy!

But the film is also thematically sleazy, with naked female AND male bosoms & gratuitous violence (for the time) aplenty, and an apathetic femme-fatale acting performance at its core, all of which feels like deliberate attempts by the filmmakers to make the movie more commercially viable than their last feature – which obviously worked, because one year later we got “The Killing”, and Kubrick’s career really took off. This doesn’t retrospectively make the exploitive touches in Killer’s Kiss any more than that, though, unlike “A Clockwork Orange” where violence is part of the narrative. That’s prevalent here, too, but more than Clockwork you can picture a metaphorically cigar-twirling Kubrick behind the scenes of Killer’s Kiss, positioning his camera a little too close to Jamie Smith’s disaffected boxer Davey Gordon’s hairy chest getting all lubed up, knowing that some smut will get punters knocking (and potentially stand later as his calling card when the “Lolita” producers rang his doorbell). Kubrick’s choice of music is still heavy-handed, even if the film’s overall audio quality is markedly improved. And it all ends without any big revelations or morals, instead boiling down to fisticuffs between two alpha-males over a hot blonde. Let’s follow this train-of-thought for a minute…

How many prominent female actresses can you name from Stanley Kubrick films? There’s Shelley Duvall, of course, from “The Shining”; Nicole Kidman from “Eyes Wide Shut”; Shelley Winters, but more likely Sue Lyon, from “Lolita”; Marisa Berenson from “Barry Lyndon”; and perhaps Madge Ryan from “A Clockwork Orange”. But that’s about it: Kubrick’s films were male-dominated casts about predominantly male issues, including emotional impotency, the links between camaraderie & violence, and feeling diminutive in the face of autocracy (and it doesn’t help the statistic that Kubrick only ever made thirteen features in his lifetime). All of the actresses mentioned including Virginia Leith from Fear and Desire and Irene Kane here (1980s’ CNN reporter Chris Chase acting here under a pseudonym) have one role, and that’s to propel the male characters to action.

In Eyes Wide Shut, it’s the bored-housewife fantasy that incites Tom Cruise to begin his odyssey. In The Shining, if Duvall didn’t lock Jack Nicholson in the cooler, the spirits may never have needed to manifest themselves physically. Sue Lyon’s horny teenager Lolita gets all the men worked up without breaking a sweat, and – by contrast – Shelley Winters’ Charlotte Haze profoundly repels them with maximum intensity; and Berenson’s Lady Lyndon is the gold nugget of subservience that Ryan O’Neal’s Barry is after. I’m including Madge since her Dr. Branom is probably the most fully-fleshed female role in Clockwork but, even if her characterization is supposed to feel some sympathy for Malcolm McDowell’s Alex mid-treatment, she’s still duty-bound to carry out the experiment: the perturbation that Madge adds to her Branom doesn’t change her character’s arc, and merely adds to its texture. The same can be said for both Leith and Kane: Leith’s peasant girl cannot communicate with the main cast of men since she doesn’t know their language; she’s scared for her life & tied to a tree; she’s also a little freaked out because this crazy dude keeps scaring her and may take things further; and she’s also thinking of a way to escape. Juggling all that in a borderline-silent performance led to overacting – same as Duvall, who sweats & pants to, and runs away from, off-screen threats that never share the same 180-degree physical space that she does.

But I need to slow down, because if I get myself all worked up – like I have over the last few days preparing this – I’ll want to jump ahead and just watch The Shining. I still haven’t seen The Killing yet. But you didn’t hear that from me…

Here in Killer’s Kiss, Kane’s Gloria Price is enigmatic, but not inexplicable. Most of the film we think she rides both sides of the fence in an effort to “stay alive” (explained by her sister’s suicide), but at the end she’s back with Davey with open arms. So wait, she really did love him the whole time? This unrealistic upbeat ending may have been strung together later to appease producers, but the fact it is here means viewers still need to treat it as canon. Kane’s smoldering pout is the secret weapon she brings to another one-dimensional Kubrick special, which in turn adds an entire mystery behind her rendering when really, according to the script, she isn’t hiding anything.

This may be a good time to mention that Kubrick – in a true display of divaship I mean, craftsmanship – fired his sound crew because the shadows from the boom mic kept interrupting his shots (which may not have happened had Kubrick not kept jumping the established 180-degree cinematography line). That means once again that all dialogue in the film was re-recorded after the footage had already been shot. This is called ADR, which I don’t want to get into again because it was my biggest point of contention with Fear and Desire: that whole film felt like the dialogue had been recorded later in a cantor that didn’t match the on-screen performances. Here, it’s much more fluid, with re-recorded lines that fit with what’s happening on-screen. It demonstrates how improved Kubrick’s use of the medium was, or who his choice of collaborators were, in the two-to-three years between his first & second films. Having said that, it is a different actress altogether voicing Gloria in the finished feature, and not Kane (the uncredited Peggy Lobbin). I’ll leave the problematic nature of this for you to consider yourselves.

The script story of “Killer’s Kiss” is credited to Kubrick himself. This means that Killer’s Kiss is actually “auteur” Kubrick’s first time seeing his shadow before standing in the shadow of executives under the studio system. You can see this burgeoning belletrism in the extended single scenes I mentioned, such as the boxing prologue (possibly inspired by his early documentary short “Day of the Fight”), and a ballet dance sequence that is specifically credited to a choreographer in the opening credits. These moments recall the second-act of “2001”, the procedural nature of the bomber in “Dr. Strangelove”, and the canvas-style framing of “Barry Lyndon”.

But when we think of later-Kubrick’s long, unbroken shots, it’s curious to note early-Kubrick’s Fincher-esque close-ups of details: or, the breakdown of his perspective through editing, rather than letting these bits of production design sit passively in the background (think the long zoom-in of Dick Hallorann in bed in The Shining). Look at Davey going through Gloria’s apartment the first time he saves her (I, too, approve of stockings, Stanley), or all the edits in said boxing & ballet sequences: later Kubrick would let these montages play out in single takes, and leave the moments of in-character contemplation as background texture.

Then again, maybe we aren’t ready to start dissecting early Kubrick’s background details, or then I’d start asking questions about the giant machete on the wall of Davey’s kitchen, or the two drunk shriners dancing to “Oh! Susanna” on harmonica (replacing the audio montage from Fear and Desire as a time-passing technique), or the Vinnie Jones-lookalike who works at a mannequin factory and busts up the climactic fight long enough to disarm Vincent when Davey just spent the last ten minutes trying to outrun him. It’s the proliferation of Kubrick the Voyeur that Killer’s Kiss will be most known for. You know I watch these things on my days off so you don’t have to.

*

What do you think? Are you a Gen-Y or a Gen-Z’er who “dabbles” in the occasional film classic, or are you one who just can’t get over the fact there’s no colour? Do you think this series could turn into something if I can manage to keep up my present record of watching one Kubrick movie every six-to-eight weeks? Leave a comment below! //wd

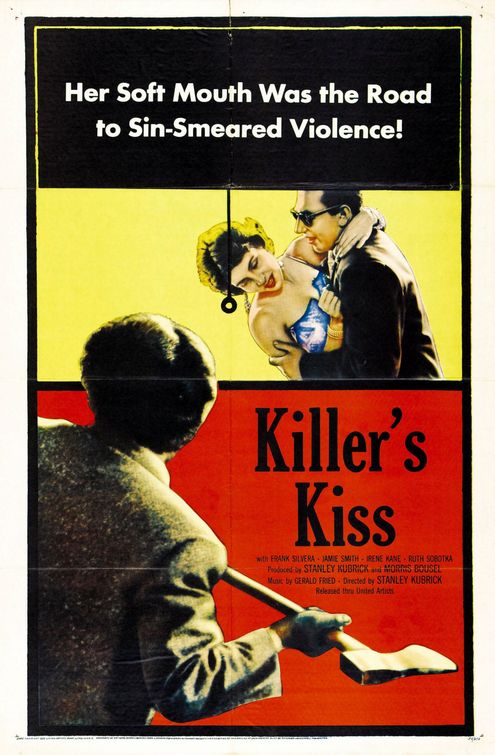

Poster sourced from impawards.com. Screenshots author-obtained. A free-to-view version of the film is available via archive.org.