A spoiler-heavy multi-scene film analysis & review.

Allow me to be a peg self-righteous for one moment, much like the aggrandizing protagonist of this week’s Selected Scenes, Harold Shand (played by the inimitable Bob Hoskins). Really, I should be writing a review for every movie I watch, at this point. There really is no excuse, especially if it’s something that I’ve been looking forward to watching. If it’s your garden-variety Netflix this-or-that then I get it: I’m maybe only looking at a couple of paragraphs (which wouldn’t sum-up to much more than the usual “I hate it, I hate their model, I hate everything” sort-of diatribe you’ve all read before), and then I need to find a way to get screenshots or (God-forbid) draw something, because this is the Internet and you need a flash screen to get people’s attention, as much as a wall-of-text is criminally-fascinating.

My point is, I’ve been watching a lot of movies lately, and I haven’t been writing about them. No wonder my upcoming scheduled posts have dried up! So while “The Long Good Friday” isn’t necessarily worthy of a 5000-word essay to this particular writer, it’s still a noteworthy entry in the British crime genre and I thought it would be fun to use the Selected Scenes framework to highlight some moments that were worth a second look.

But wait, wasn’t that the point of this series to begin with? To examine a movie’s most memorable moments from one particular point-of-view? Well yes. And while The Long Good Friday is not high-art, it is a pulpy, raw drama, that is well-highlighted in certain circles for inspiring other notable filmmakers’ bibliographies. Anyone I can mention in-particular? Part of the problem with writing these (which I’ve said before, and will say again) is the balance that must be struck between anecdotal evidence and actual hard research with citations. So if we’re being honest (as I’m want to), I always check the “Trivia” column of a movie’s IMDB page before I write these – and often before watching the actual movie, out of a pure damnable attitude toward ruining things for myself. How does IMDB track the viability of a piece of trivia that someone submits? I’ve never asked myself this question before. Sometimes some cool trivia is all it takes for me to want to watch something (like learning Lee Majors was drunk for most of “The Wild One” shoot, and after watching it I can say that I agree). So how does the process work for getting your trivia blurb published? Do you have to include a citation in your submission for that very reason, or is it like the Wild West that is Wikipedia where one day your page looks normal and the next someone has drawn a cock-and-balls in ASCII and the moderators haven’t taken it down yet? So, in the vein of someone casually coming across a Facebook post that may-or-may-not be true, I just take the IMDB trivia at face-value. Most of the trivia I garnered for The Long Good Friday was, admittedly, kind-of cool (like how North American distributors wanted to put Pierce Brosnan’s name first in the credits because Yanks knew him from Remington Steele, even though his role amounts to one line and five-minutes of screen-time), but that’s not why I wanted to watch it. It was because of the DVD cover.

Yes, I’m sure I first saw this on some DVD review site way-back-where, when I frequented such online journalistic endeavors like dvdtalk.com and dvdtown.com. And at that impressionable age, a home video release calling itself the “Explosive Special Edition” with an overly-aggressive shot of Hoskins (I didn’t give a shit about Helen Mirren back then) was enough to make me want to watch it. I didn’t know Hoskins from much: Smee in “Hook”; Mario in the “Mario Bros.” movie; Eddie Valiant in “Roger Rabbit”; kids stuff. But I always liked him and I can definitely call the late actor someone I would gravitate towards when I knew he starred in something: that short-guy swagger; the Cockney accent; and his no-bullshit way of speaking. He carries The Long Good Friday in its numerous close-ups: plotting; scheming; trying to think ten-steps-ahead of the Irish crew that threatens his empire over the film’s ticking-clock 48-hour window. And despite this closeness with the audience, he’s not easily-sympathized with. Like most antiheroes, he has his own corrupt moral code that he operates by: the aforementioned self-righteousness that guided his Harold to buy a piece of land by the London docks for an Olympic bid that went sideways (in an attempt to go-legit, like any reputable British mobster in the movies), only to show how antiquated and skewered his worldview is the next (dropping a car on a Black kid’s head because he doesn’t pony up the information he wants). My corrupt moral code would tell me that it’s OK not to do a write-up for EVERY movie I watch, for whatever reason (convince myself that it’s too much work; hold myself to the expectation of having a picture AND citations for every review), while on the other hand, who really cares? Maybe it’s because my last couple have been for movies that hold themselves to a higher-level of interpretation, while something like The Long Good Friday has great acting; a couple of comparison-points to be made to modern cinema; and some great isolated moments of awesome; and, well, that’s about it. If that’s enough to make me remember a movie, then it should be enough to tell you all why it’s worth watching. It’s pure entertainment, and by its end all of its dangling plot threads are tied up and you know exactly what it was they were going for with nothing left to the imagination. And while I can’t confirm-or-deny that it inspired some notable contemporary directors, we can definitely spot some similarities.

Hey Hey, HandMade Films: former-Beatle George Harrison’s production company. Trivia says he wasn’t so happy when he found out how violent The Long Good Friday was, and that he never would have produced it had he known otherwise. I remember the logo most from “Monty Python’s Life of Brian” and “Time Bandits”, so that tells me it was synonymous more with unconventional British cinema as opposed to mainstream fare. With that being the case, it seems like the perfect fit.

While he’s not the first thing we start with, Hoskins’ first appearance is the most direct the film is with the audience since it starts, almost ten-minutes in. His “crimelord” Harold is back from a business trip to the States that could mean the deal of a lifetime. Harold is straight with us as soon as the carnage starts: who would want to hurt him? He thinks about it. There isn’t anyone left alive who challenges his empire anymore: at least no one he can remember. His bid at legitimization isn’t so much a vertical move as a lateral one: there isn’t anywhere else left for him to go. He has the police and the construction workers’ union in his pocket; he has the money and the resources (his empire is spread across multiple factions around London, like the franchisees of a restaurant chain); and he has managed to stay clear of selling drugs (the defacto no-no for many of these mob movie archetypes), concentrating mostly on racketeering. As far as he’s concerned, he stands to make so much money over the next few years that he doesn’t mind throwing around a percent of the business here-and-there so long as it gets him what he wants now. More power, more control. More. But even as he exits his flight and walks through the airport during his first appearance here, he keeps looking over his shoulder in a way that doesn’t look like he’s looking for his ride, or inspire confidence in the viewer that he is sure of himself. “If you’re good, you’re always looking over your shoulder.” (-Bruce Springsteen) But what do I mean when I say this is “the most direct” the film has been?

Because there’s a whole prologue about a mysterious briefcase full of money that trades hands between faceless characters we can neither name, nor place. Who are these people? Why are they counting the money in an unmarked cottage in a nondescript countryside, and then held up at gunpoint by another anonymous group? This, while the film cuts a montage between it and the murder of one of Harold’s accomplices: the “inciting incident”. And then there’s a funeral, and a widow shows up to spit in the face of another unknown mob guy while a strange, scarred man watches from across the street. What is going on?

It’s all very Guy Ritchie/Quentin Tarantino-esque, where the audience doesn’t have all the information yet. But little do we know that all the main players are introduced in this opening sequence. And it’s a lot to process, too: these are just random faces to the viewer at this stage, and we have to put our trust in the movie that it will explain things to us as it goes on. Aside from the lack of a flashback-structure (which seems commonplace to us now in the realm of British crime movie tropes), there is much to take from just these first ten-minutes as a sort-of “jumping-off” point to the structure of many modern crime movies: the briefcase, or the “red herring” that puts the plot in to motion while not actually being what the story is about; the protagonist’s arc of redemption while being wholly-irredeemable himself; the “traitor-in-the-ranks” plot twist; even the scarred man, who we find out is an enforcer for Harold named Razors who suffered the same machete torture that he doles out himself, speaks in an indecipherable tongue that brings to mind Brad Pitt from “Snatch” and Colin Farrell from “The Gentlemen”.

It’s all very characteristic and to a degree self-aware, to the point where these films play with audience expectations since we’ve all seen so many of them now. How can they top themselves? I’m trying to think of other outlandish British cinema with a real-world story bolstered by odd details and I’m coming up with “Trainspotting”; “Filth”; “Layer Cake”; “28 Days Later”…. The Long Good Friday stands at the feet of giants. IS the feet. Maybe not the soles though, I’m sure there are old black-and-white classics that laid the real foundation. But you can see how The Long Good Friday could have inspired its contemporaries.

Trivia time (from the pages of IMDB): apparently American distributors were lined-up to re-dub Hoskins’ voice with a more-comprehensible actor fearing that us Colonials wouldn’t understand the Cockney accents and slang the film uses. Why just Hoskins? Why not P.H. Moriarty (the actor who plays Razors) too? Why not any of the other actors and actresses speaking in their native tongues? I would not have wanted to be a third-party to that meeting, where Hoskins must have told producers in no-uncertain-terms that his voice WOULD NOT be overdubbed. Life imitating art.

Speaking of trivia, there’s Bond #5 himself (#6 if you count David Niven, but if you count Niven then you have to count Peter Sellers and, yuck, Woody Allen, too). This was one of Brosnan’s first, if not THE first, film role and… well, he’s pretty much just used as man-candy, isn’t he? Even my wife asked if he still keeps this movie on his resume. Here he plays an IRA operative, seducing Harold’s gay friend Colin before shanking him dead. He has aged incredibly well, if the criteria for aging-well is how good someone looks in their 60s and 70s when compared to their 20s and 30s. But yeah, he’s hardly in the movie, and I can imagine the DVD cover looking a little different if it was HIS name listed first instead of Hoskins: more like that direct-to-video garbage you find at low-cost retailers like Fields and The Bargain Shop in a big bin marked for a dollar each, with his name taking up a third of the box and then a list of all the big movies he’s made since, printed in tiny font just underneath. What? James Bond is in this movie? I loved “Die Another Day”! “Then you’ll love The Long Good Friday, a lost-treasure in the Pierce Brosnan filmography!”

Helen Mirren is in this movie, too. Another fun fact: apparently her uncle was a notable British gangster. I mean, I haven’t read anything on it so I don’t know how openly she talks about him or how much of a role he played in her life growing up or even in how she became an actress in the first place. I’m not going to read too much into it because she’s still around, she’s a national treasure, and any movie she’s in is immediately raised in stature. Even if that movie is “Caligula”. Now THERE’S a fun subject for a Selected Scenes: maybe once the new version that kid prodigy is re-editing gets released. I’d like to think that Helen Mirren has had her breasts out in every movie she’s ever been in but that’s a lie: those are just the movies I remember her from most: Caligula; “The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover”; and from playing the badass grandma in “Fast & Furious 8”, “RED”, and “Anna”, among others I’m sure. Oh, and as The Queen in “The Queen”. She’s a great actress and I have nothing negative to say about her performance in The Long Good Friday: she plays Harold’s wife, but as the kind of woman who’s really in-charge behind-the-scenes and knows when to cut a dinner party short. When Harold flips out later in the movie and smacks her, not only is she genuinely hurt, but Harold’s reaction is not what we would expect: he’s remorseful. He would never treat his wife like that, nor has his wife ever had to put up with that kind of behavior. Obviously the ordeal is taking its toll on them. This is the sort of gravitas that Mirren adds to the role and makes it more three-dimensional than your average gangster’s moll (which is almost verbatim from the IMDB trivia listing that said she wanted the role to be more three-dimensional).

While we’re still talking acting, I was wondering who the guy on the right was til I realized he was the Chef on the second series of “Fawlty Towers”. I don’t know what to do with this information now that I know it. Probably forget it. But it’s worth mentioning. His name is Brian Hall and he has also since passed.

But we aren’t here for “actors” or “plot” or whatever, we’re here for the good stuff aren’t we? And The Long Good Friday has awesome set-pieces in-droves. Here are some highlights:

A very-cool shot of one of Harold’s bars exploding from a planted bomb that misses him and his party by mere minutes, seen from the front-seat of his car. The shot sequence definitely foreshadows the explosion, but when it happens it’s still unexpected and packs a punch.

Harold rallying the troops, telling them all to go squeeze their rackets for whatever information they can find about the murders and the bombings. Not only does he tell them to “bring the guns back” when they’re done with them, but he also tells them to “be discrete”. OK sure.

This leads to a section in a slaughterhouse, where all the various low-level bosses of the organization are strung up and threatened to give up whatever they know. We get a cool upside-down first-person shot of them being wheeled into the main room, and a right-side-up tracking shot of their faces as they’re hanging there, becoming red and bloated from the blood rushing to their heads. How did they shoot this scene? Did they use dummies for some shots but the actual actors for the tracking shot? And boy, some of them did not look like they were having a good time.

Once Harold gets wind that his second-in-command was partially-responsible for the attacks, he confronts him in a scene that ends with him smashing a bottle over his head and stabbing him in the neck with the broken end. The sudden violence of the scene is one thing – as is Hoskins’ reaction to the murder afterward – but special mention should be given to the blood effects, including a spitting artery that looks really good. Professional, I mean. And to think this movie was made in 1980 and they could all make practical make-up effects look like that, if they tried. All you needed was a little effort.

Harold arranges a meeting between the London IRA chapter head where he makes him believe he’s buying him off when in reality the plan is to murder him in-cold-blood (thinking this will somehow solve his problems, as it has before). Razors bursts through the conference hall door, which is on the second floor of a tower overlooking a demolition derby race, and shotgun-blasts the IRA guy through the window and down to the track, directly in-front of a speeding car, causing a three-car pile-up and explosion as they swerve to miss the body and fail. It looks really cool but it’s shamelessly-gratuitous and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention it. Unnecessary entertainment!

And finally, thinking he’s won the day and can still save his deal with the Americans, Harold goes to their hotel room only to find they are packing up and leaving: his business is too messy for them. Harold flips out: the Mafia is scared of some bombs going off? There isn’t anything particularly noteworthy about Hoskins’ angry monologue to them – other than his saving-face under-the-surface – but the reaction shots of the Americans is priceless. They’re just hanging out, politely listening to him yell at them and calling them “piss”, I suppose because nothing at this point will change their minds (and if anything, Harold’s tirade just confirms their suspicions that this may not have been the profitable venture they were hoping for).

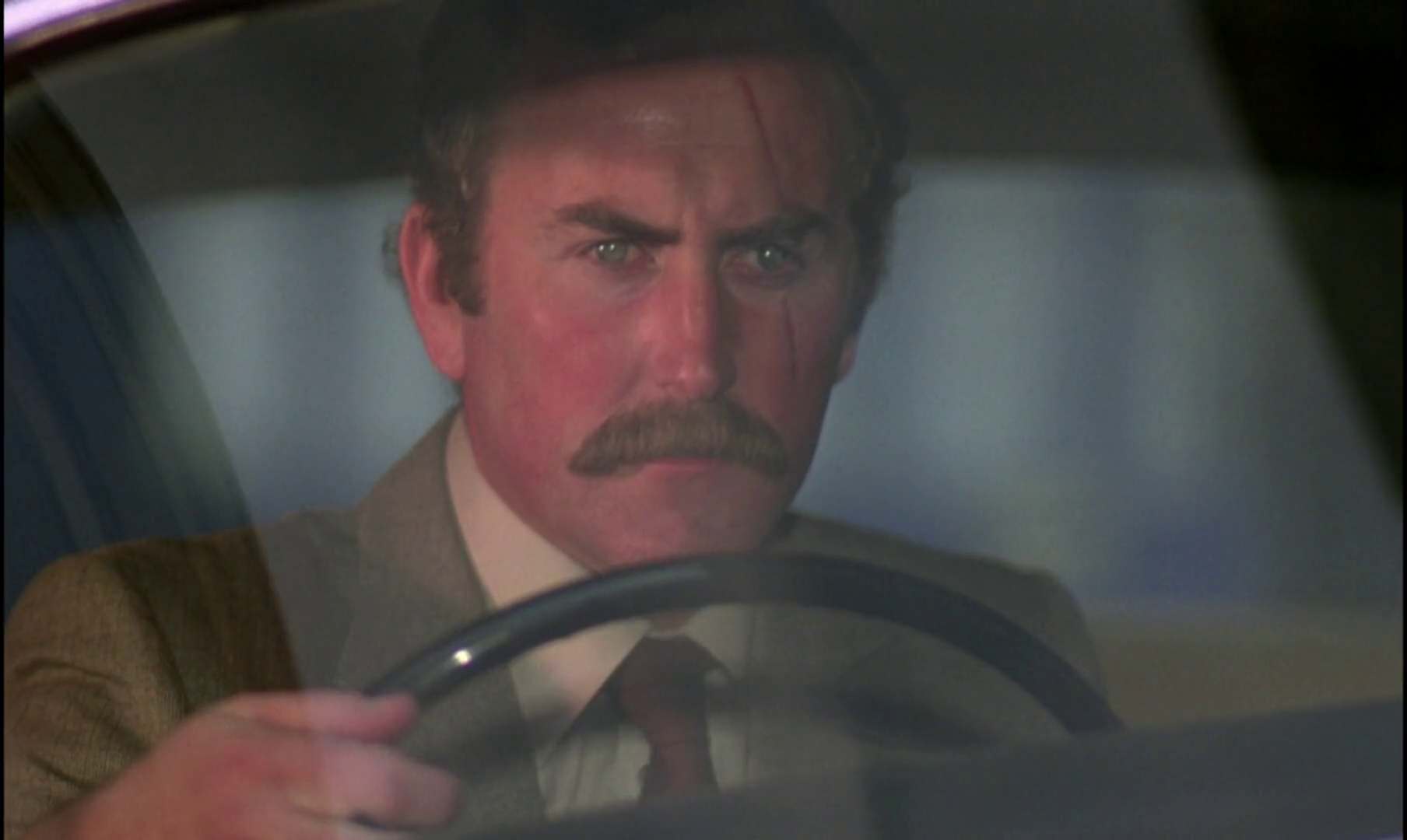

All in the space of 48-hours, Harold’s empire comes crumbling down, which goes to show how it can all go up in flames if you aren’t constantly keeping an eye on what’s yours (and sometimes, as we saw in the airport at the beginning, even looking out doesn’t work all the time). It turns out that the IRA moving-in on Harold’s territory doesn’t have anything to do with Harold personally but a power-play (a red herring of its own, then), with him seen as a barrier to be overcome, or a fence to be hopped over. This realization swiftly changes the film’s thematic trajectory from revenge to tragedy: anyone could have taken Harold out, just so happens it was the Irish. After denouncing the Americans, Harold gets back into his car only to find his wife has been kidnapped and in his front seat are the Irishmen who killed Colin, with Brosnan looking over the seat with a gun to him. The movie ends with a long shot of Hoskins’ face as his Harold runs the gamut of emotion: from exasperation to conniving to accepting of his fate and then back again. A few movies have done this recently: an unbroken shot of our protagonist at the end of his journey segueing into credits (“Michael Clayton”; “Call Me By Your Name”), and it shows you don’t need much more than the expressive face of a committed actor to tell you how they’re feeling after the gauntlet.

So was The Long Good Friday, well, good? It was. There were a couple of things I suppose I could complain about (some of the pacing; the age of the picture; how we’ve seen some of this stuff a million times since) but we’re at the end of the article and I haven’t felt the need to complain about it yet, so I won’t. I was pleasantly-distracted, and my wife even watched the whole thing with me so take that as extra incentive if you want. All I know is I’ve written about 2000 words more than anticipated. Until next time!

//jf 8.5.2020